Book Review: Brian Spears' "A Witness in Exile"

Travis Griffith

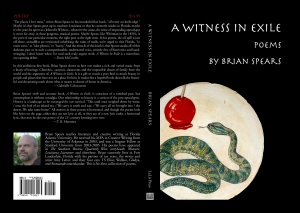

Brian Spears, whose debut book of poetry A Witness in Exile was published earlier this year by Louisiana Literature press, is no stranger to long-time readers of Relief, having won the editor’s choice prize for poetry back in issue 2.2 for his poem “Hall Raising”. Although the poem published in that issue didn’t make the final cut of the book itself, many of its themes are revisited in A Witness in Exile, and handled in a way that Relief readers will probably find sincere and compelling.

Keep reading for the full review!

Though not explicitly divided, A Witness in Exile cleaves into roughly two sections. Poems in the first half of the book, with some exceptions, often focus on the relationship between an individual and an environment. As his biography indicates, Spears has a diverse background, and he presents poems set against the bayous of Louisiana, the swamps of south Florida, the deserts of New Mexico, and the coasts of San Francisco—places that “teeter on knife-edge” (to borrow a line from one of the poems). Sometimes these poems feature people; sometimes they meditate on the locations themselves. A sensation of loss pervades even those works peripheral to this motif, however, and the composite effect is of a writer seeking peace and completeness, in an existence that is wandering and fragmentary. On first read, this makes the book itself seem initially somewhat rambling, filled with poems that are occasionally quite strong—but collectively disjointed.

Unity emerges, though, in the book’s second half, where the poems take on a more consistent poignancy and urgency. Throughout this second half, Spears addresses material centered on his own childhood as a Jehovah’s Witness, a life he subsequently rejected, and he confronts this subject matter clearly, honestly, and un-ostentatiously. There are poems drawing from the religion’s core beliefs and practices, as well as its liturgical rituals and personal struggles. Most moving, though, are the poems that deal with the personal wounds that open when a prior believer walks away from the culture, and in this case the family and home, that raised and loved him.

Admirably, the Jehovah’s Witness poems (if it’s fair to label them as such) never descend into simplicity or caricature, and simultaneously never lambast or criticize. Spears—or, more to the point, the speaker in his poems—understands the beauty of the people who inhabit the lifestyle he is abandoning, and wishes them no harm. Indeed, some of the poems’ strongest moments come when the speaker seems to wish that he could go back to a time when he was unquestioning, to a clear-cut life undiluted by the complexity of doubt, when spiritual boundaries were clear, and—as the speaker freely admits in one poem—he was the happiest he’s ever been.

Admirably, the Jehovah’s Witness poems (if it’s fair to label them as such) never descend into simplicity or caricature, and simultaneously never lambast or criticize. Spears—or, more to the point, the speaker in his poems—understands the beauty of the people who inhabit the lifestyle he is abandoning, and wishes them no harm. Indeed, some of the poems’ strongest moments come when the speaker seems to wish that he could go back to a time when he was unquestioning, to a clear-cut life undiluted by the complexity of doubt, when spiritual boundaries were clear, and—as the speaker freely admits in one poem—he was the happiest he’s ever been.

It is common to read Christian-themed poems about a believer’s doubts, and the trajectory of such poems is usually predictable. Less common, though, are poems about doubting ones atheism, and Spears’s inversion of the conventional tropes is tender and surprising.

When these two halves of the book are taken together, they enhance one another nicely. The first half presents speakers and poems who, at their center, seek a temporary version of the peace at one point possessed and then scorned in the book’s second half. The book seems to keep the reader at arm’s length for the first thirty pages, where its sadnesses are often ill-defined; someone is wandering off in exile, yes, but it’s hard to say from what. In the back thirty pages, however, the speakers are much more precise with their longing, inviting the reader into their intimacies, and this adds new texture to the initial poems. This juxtaposition creates a book that can exist as a completed text, in addition to a collection of isolated works.

It may be tempting to interpret the composite impact of Spears’s work from a purely spiritual vantage—as an account of the emptiness that dominates when Christ is not accepted, for example, or of the limitations of a particular sect of Christianity. Such interpretation, though, would be an oversimplified mistake. A Witness in Exile is the rare book of poetry that succeeds in treating matters of spirituality with tact and subtlety, coaxing a legitimate emotional response through its depiction of a worldview, not a dogma. It is a book not about the comfort of belief, but of the costs and consequences of a specific unbelief—costs that manifest themselves not in the hereafter, but in the sometimes melancholy here and now.

A Witness in Exile is available through www.amazon.com, and through the author’s personal website, www.brianspears.wordpress.com. I highly recommend it.

***

Alan Ackmann was fiction editor for volume two of Relief: A Quarterly Christian Expression. He teaches in the writing department at DePaul University. His fiction has appeared in numerous literary journals, including Ontario Review and McSweeney’s, and he recently completed his first novel. His website is www.alanackmann.com.