The Portraits Look Back

J. MARK BERTRAND

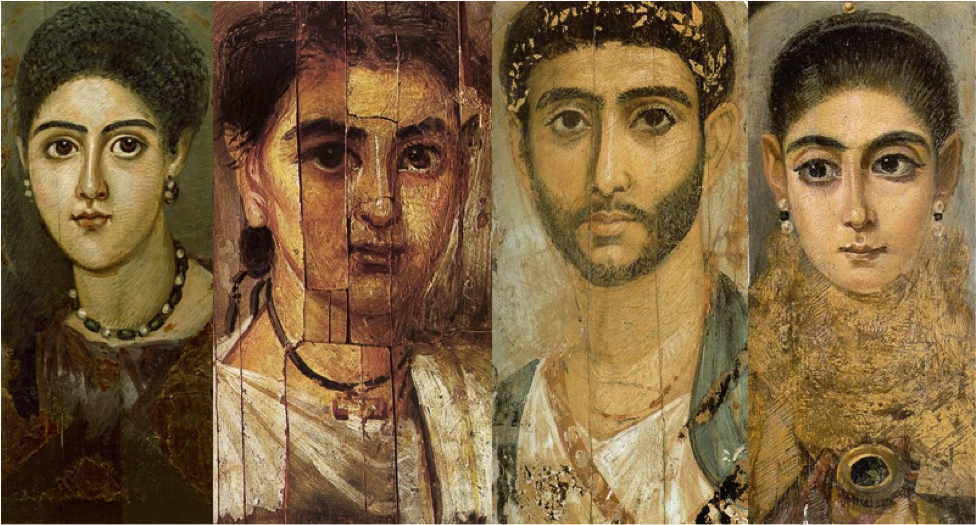

Greco-Romans in Egypt during the first few centuries after Christ commissioned artists to paint their portraits, often in encaustic, on wood panels that were then affixed to their mummified bodies. These mummy portraits, though painted after death, depicted living subjects, their closed eyes re-opened (and in some cases, mightily enlarged) by the artist’s brush. Comparative studies suggest that, while the paintings are somewhat stylized, they bore a strong resemblance to the people they represented. The old were depicted as old, the young as young, and a facial reconstruction of at least one mummy is a dead ringer for the man in the portrait. The Fayum mummy portraits, in other words, are fairly accurate pictures of people who lived nearly two millennia ago, painted in a style that could pass for contemporary.

The most striking thing about them? They look like us.

There’s only so much enthusiasm I can muster for landscapes and still life, though I realize some people can stare for hours at a lovely field or some artfully posed pieces of fruit. Only portraits hold my attention that way, and I think I know why. When you gaze at a portrait, the portrait looks back at you.

The most haunting artifacts of the ancient world are the human forms cast from hollows in Pompeii’s volcanic rock. The victims of Vesuvius, trapped in molten amber, emerge as rounded fetal abstractions, anthropomorphic depictions of raw emotion. Those hunched, cocooning forms preserve not just a horrific moment in time but also a universal feeling of helplessness in the face of death.

If the death portraits of Pompeii speak through abstraction, the power of the mummy portraits of Fayum comes from their particularity. They didn’t catch their subjects unaware in a moment of time. They depict people as they were in life, a host of individuals making eye contact over the span of centuries. These paintings preserve not just the form of the ancient men and women, but also their gaze.

When I put myself into the place of the Fayum artists, it’s hard to imagine them thinking in terms of “doing art for the ages.” Their work seems to have been part of the ritual surrounding funeral preparation. They were craftsmen adjusting set visual rubrics to resemble as closely as possible the features of the deceased. Like the embalmers and the makers of death masks, they had more in common with today’s mortuary cosmetician than with a painter exhibiting work in a gallery. And yet, uncannily preserved by the dry Egyptian climate, their work turned out to be for the ages after all. We do not know their names, yet they gave their subjects a kind of immortality.