The Universe Unending

William Coleman

The week was thick with doubt; I couldn’t see past my nose. On Sunday, I’d begin a two-night run as Cyrano de Bergerac within a majestic, historic theatre, upon a stage framed by a gilded proscenium, before an audience seated upon velvet chairs beneath a central dome of stained glass. What justice could I possibly do (I could not stop thinking) to the grandeur of that play’s great space—the one built when my city was young, and the one Rostand made of words?

And so, on Thursday, I found myself printing a dozen copies of Thomas Hardy’s “In a Museum,” and setting the tiny stack in motion, hand to hand, counter-clockwise, around my classroom’s oaken table. “Listen to this,” I said to my students, and to me.

I

Here's the mould of a musical bird long passed from light,

Which over the earth before man came was winging;

There's a contralto voice I heard last night,

That lodges with me still in its sweet singing.

II

Such a dream is Time that the coo of this ancient bird

Has perished not, but is blent, or will be blending

Mid visionless wilds of space with the voice that I heard,

In the full-fuged song of the universe unending.

As I read, the waves of Hardy’s words, a century after they found lodging in his page, fledged into the room, pushing and pulling air, winging their way toward the heat they would become. Such a dream is Time.And when we spoke of resonance, of memory’s essential mystery (fossil-moulds of time we carry unseen until recollection breathes them into being and their life is brought to ours)—when we spoke of the unending blending that makes us whole, our words’ wakes merged the space between us, and then went on, beyond our knowing.

We go on, I hear Beckett’s speaker of The Unnamable say from somewhere I cannot name, for he never said it quite that way. Was he even speaking at all, I wonder, that voice who came to feel composed solely of words that came before it? “Is it possible certain things change on their passage through me?” he wonders. Certainty; doubt: the space between, a dream.

My sophomores adore Rostand’s play. Each year, when we finish reading it aloud, half are actually in tears, half are outraged. “I hate the ending!” they shout to one another before shouting at me. And then: “Can we read it again?”

I know something of what passes through them as they read. At seventeen, awkward, gangly, with a mother dead and a grieving, distant father, with pages of poetry and albums of songs for company, I read of a man who disappeared into words, and of a beautiful woman waiting for him there. It sustained me for a time.

That Thursday in the week of my uncertainty—those final days before Rostand’s words would have to make their passage through my consciousness and history toward those of family and friends and strangers, so many strangers—I needed to keep going. And so I entered that tiny museum of Hardy’s finding: that vast space where ancient breath is held and breathes anew, given our breath. Every poem worth its salt is such a space. Every play. Every life, real or imagined. The least we can do is go on.

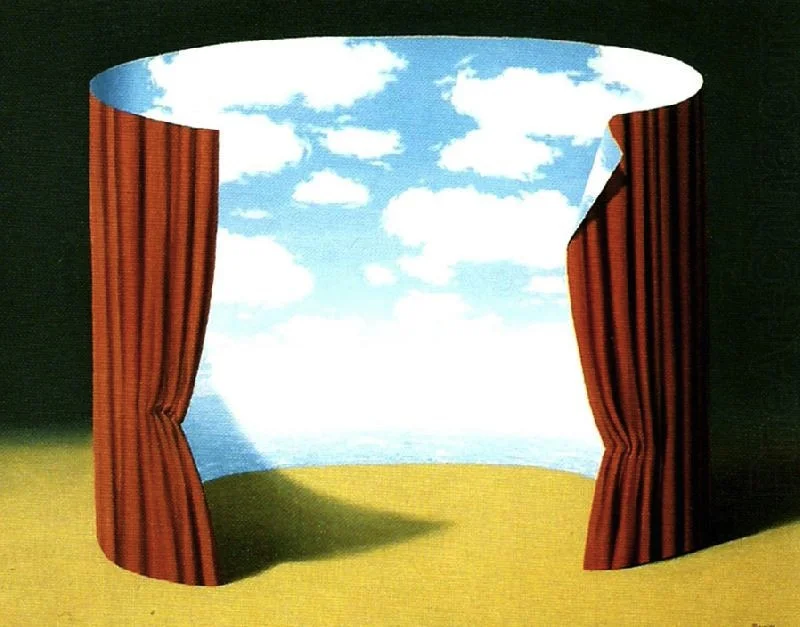

(Painting by Magritte)