From a Place of Anger

Aaron Guest

I write this from a place of anger. And I think it’s a good place for me to write from.

I write this from a place of anger. And I think it’s a good place for me to write from.

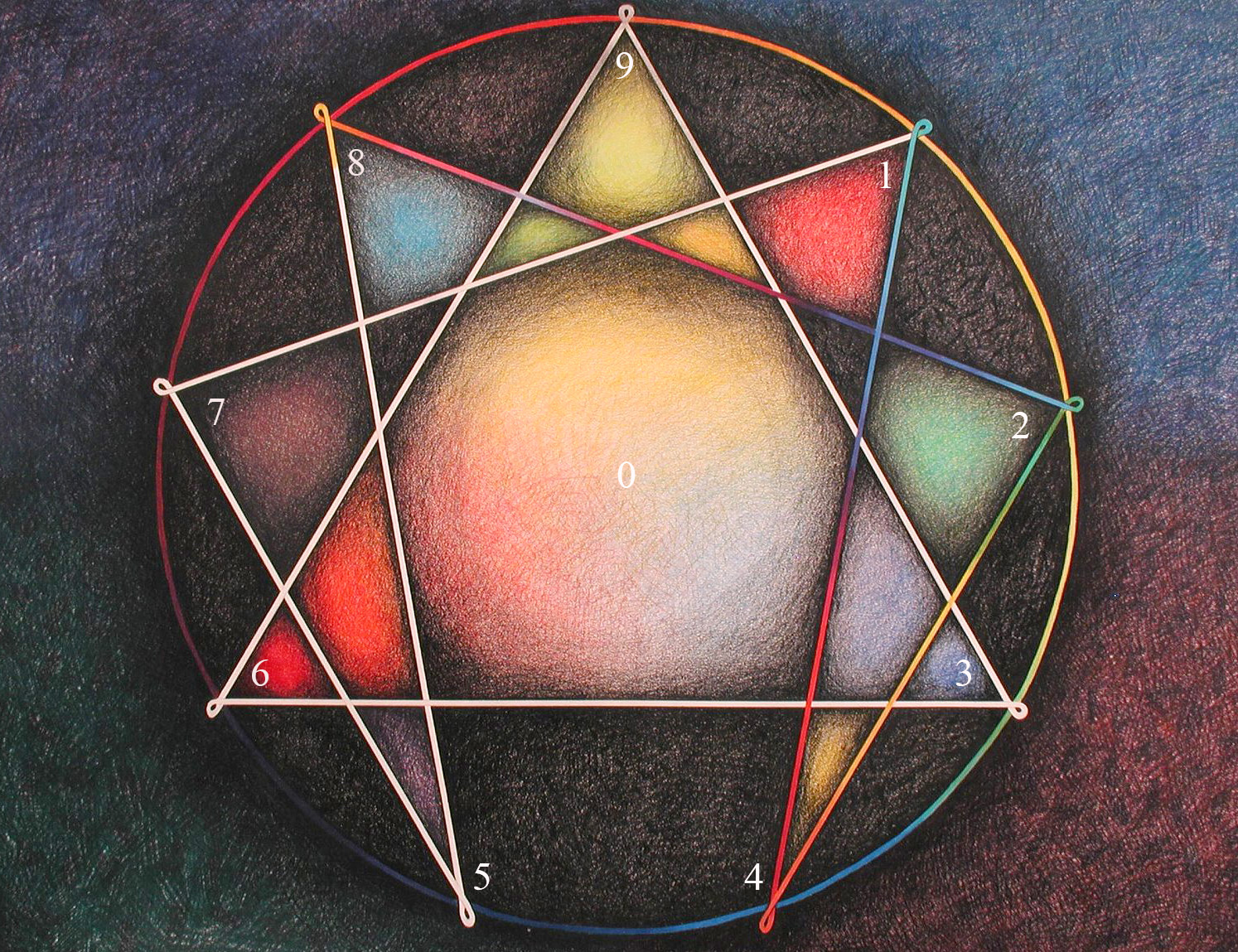

Over the past two years I’ve been able to invest more time into understanding myself. It began when a friend introduced me to the Enneagram. It’s a personality test that assigns one of nine “types” to people based solely on their motivations. From “The Perfectionist” to the “The Peacemaker”, it definitively accounts for the way I, and others, behave.

The Road Back to You is a sublime primer on the Enneagram. Written by Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile, it’s witty and informational and I highly recommend it. The book explains the way the Enneagram demonstrates the spontaneous and unpredictable beauty of being human, and how it can flourish and flounder in a predictable away.

Discovering my type has changed the way I understand myself. For example, as a 9 (“The Peacemaker”), when it comes to anger I have an innate ability to dissolve it. To bury it and effectively pretend that it wasn’t a big deal. Sometimes it’s not. But sometimes it is. Like today. The day after the election. This is a big deal and it can’t ever not be.

I also have this incredible ability to put everyone’s desires ahead of my own. I rarely ask myself what I want to do. None of these are de facto negative qualities, but they can be. And my tendency is to let them cripple me. To let them prevent me from doing something, from speaking up.

The Enneagram has also shown me how the people closest to me are very different from me. None of us are the same types. And the Enneagram is at it’s absolute best when it’s showing how the types respond to each other in relationships, in decision making, in conversation. It has become the single most useful tool to help me listen and understand the people around me. We are different. We are each our own type, with our own motivations for action and inaction, for decision and indecision, for happiness and sorrow. The Enneagram advocates for empathy. It lights a path to loving our neighbors in a very real and bright way.

One day soon I will see that the evangelical church I am angry with is made up of different people, with all types of wants and fears. But today, in the days after election day, the Enneagram is teaching me about being honest with my anger. To kick over a few tables—to borrow from a famous scene in the Gospels. American evangelicalism has made a mockery of my faith.

So much of my life as a Nine is to seek peace. To deny my anger because it brings disharmony to my life. But, what looks like my desire for peace is really just a desire to shy away from conflict. Should I pray that this anger translates into action? As a nine, when I move toward action because of anger, I enter into a state of becoming. I awake, soul intact and strong and true, into a better person. And I realize that behind all true peace there must be pain and conflict. As Fr. Richard Rohr says, “The only way to overcome the bad is to be the better.”

May I need to want to be better. May I need to want to not be scared. May I need to want to speak up and fight and change this.

Lord, let me stay angry.

Train us Lord to fling ourselves upon the impossible

Train us Lord to fling ourselves upon the impossible Though I am as dismayed as anyone by the current election year antics, I take comfort in remembering that bald-faced lunacy exercised in high places is nothing new. But I still have the sense that this election cycle is in a league of its own. Hopefully the bilious clouds of insanity swirling around us this fall will one day coagulate to something Americans can still recognize, once the whole thing is relegated to the history heap.

Though I am as dismayed as anyone by the current election year antics, I take comfort in remembering that bald-faced lunacy exercised in high places is nothing new. But I still have the sense that this election cycle is in a league of its own. Hopefully the bilious clouds of insanity swirling around us this fall will one day coagulate to something Americans can still recognize, once the whole thing is relegated to the history heap.![By Colin Mutchler from Brooklyn, United States (Flickr) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://static1.squarespace.com/static/5898e29c725e25e7132d5a5a/58aa11bc9656ca13c4524c68/58aa12239656ca13c4525ec7/1487540771442/Mlk_quote.jpg?format=original)