The Messiah

Christina Lee

As a college freshman, I was assigned a class called “Choral Union.” I assumed this was some sort advocacy group that made sure everyone had fair access to sheet music and water breaks during rehearsal. Whatever it was, I—as a new music major—was game.

It turned out to be conscription in a weekly three-hour evening rehearsal of Handel’s Messiah. The “union” merely signified that the whole community, regardless of musical ability, was invited to join up.

This should have sounded fun to me. But it did not. I’d never heard the term “oratorio.” I’d never seen a performance of Handel’s Messiah. Of course I’d heard the “Hallelujah Chorus;” I’d even sung it. But I had no desire to spend three hours a week singing the “Hallelujah Chorus,” fun as it had been. That seemed excessive.

As I’d feared, rehearsals were tedious, often dragging on past their promised 9:00 dismissal. Our zealous, rubicund conductor was nothing if not thorough. Movements were broken up into tiny chunks, every measure picked apart for its diphthongs and dark vowels and sagging pitch. Hours were lost on a single page of the score as earnest, tune-deaf community members gave it another go.

To be fair, the music was hard. Much harder than what I was used to. I wasn’t so great at it myself. Inevitably, right when I would catch the tune, we’d be angrily cut off with a baton tap and a vociferous, “like women, please, not little girls.”

Our conductor’s face would purple as he reminded us, “it’s the KH-LORY of the Lord. Not Gulory. KH-lory.” As everyone around me earnestly took down this note, I doodled sad little sketches of angry penguins in the margins of my score.

Is it embarrassing to me, now, my attitude? To think that I would have preferred to be back in my dorm room, gossiping about boys and listening to Savage Garden? Of course it is. It’s mortifying.

The real embarrassment? I so utterly lacked curiosity about the work we were preparing to perform. It never once occurred to me to sit down and listen to the piece, so I couldn’t hear the beauty we were working towards as we picked at it in rehearsal.

I’d like to tell you that, on the night of the performance, I was struck by the glory of the score and I repented of my grouchiness. I cannot. I was so fed up by then, so jealous of the soloists mincing out in their shimmery ball gowns, so tired of being yelled at to sound “more like a WOMAN,” that the performance was blur.

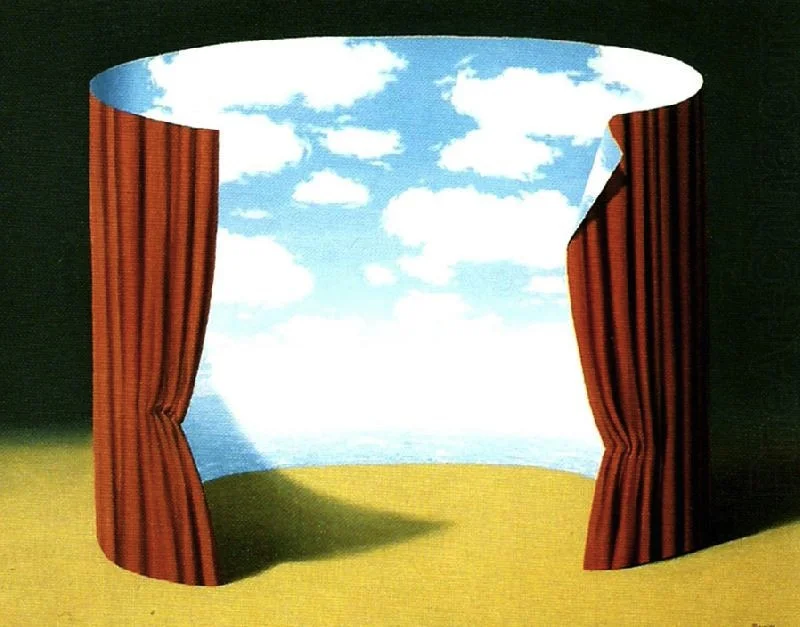

My conversion came years later, when a friend invited me to attend the Los Angeles Master Chorale’s “Messiah Sing-a-Long.” The thought of the music still made me a little nauseous, but I’d always wanted to see the Disney Concert Hall, so I went. The hall was filled with giddy Angelinos clutching their battered Messiah scores. As we launched into the first movement, I noticed two things. First, the notes came back to me as if I’d rehearsed them yesterday (confirming my grudging suspicion that that conductor was a very talented man). Second, this music was glorious. It was soul-rending to lift my voice with these 2,000 others. It was euphoric.

As rich, rippling chords splashed around the curved walls of the hall, I glanced at the score for my next cue and caught a glimpse of the angry penguin brigade, circa 2002.

And I remembered grumpy little freshman me, surrounded by all this glory yet totally deaf to it.

If you have a few minutes, sit down and listen to my favorite movement: “Surely He Hath Borne Our Griefs.” I dreaded this piece most in Choral Union. I slouched through it, rolling my eyes as our long-suffering conductor barked out, “CH-UR-LY, people. Not Surely. Ch-ur-ly!”

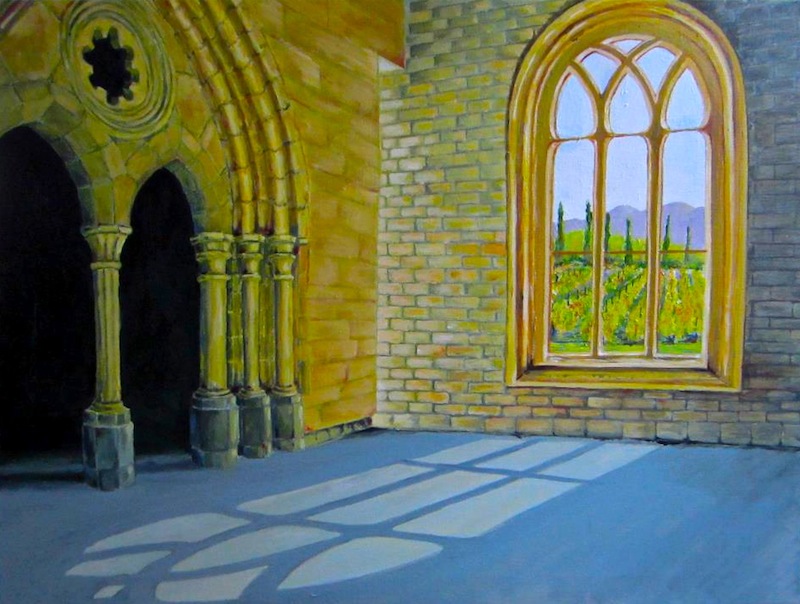

Sometimes I listen to remind myself that, while grueling, measure-by-measure rehearsal is necessary, it isn’t the end result. And you can’t let yourself drown there, in the details.

When I listen now, I think about the classes I teach. I think about the family relationships I’m working to mend. I think about the poems in my “keep revising” desktop folder. I listen to remind myself not to stall out in the measures I’m slogging through, so I’ll be able to hear the beauty when it comes.