The Little Drummer Boy and Me

Jessica Brown

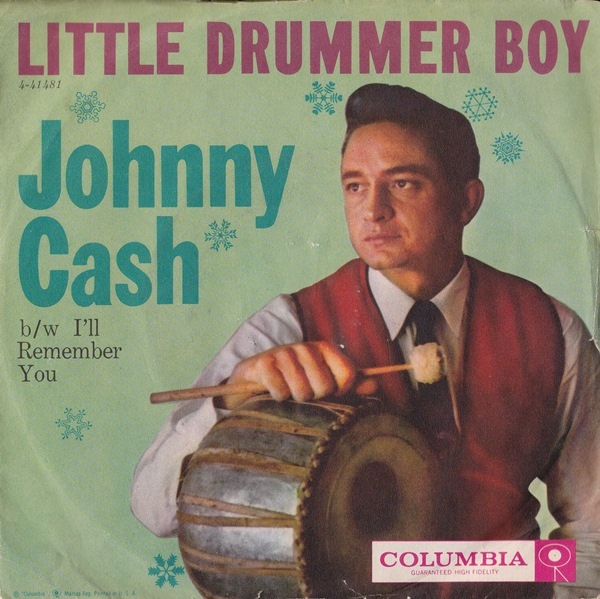

A few Christmases ago, I heard Johnny Cash’s version of “The Little Drummer Boy” for the first time—and heard words in the song I never had before. That gravelly voice brought a certain realistic cadence to the carol, the cadence of a human soul before the Son of God, lying as he is in a container that holds food for cows and donkeys. And it’s also, I realized, the cadence of a musician, an artist, giving what he has. (The video of Cash singing the carol is well worth watching.)

A few Christmases ago, I heard Johnny Cash’s version of “The Little Drummer Boy” for the first time—and heard words in the song I never had before. That gravelly voice brought a certain realistic cadence to the carol, the cadence of a human soul before the Son of God, lying as he is in a container that holds food for cows and donkeys. And it’s also, I realized, the cadence of a musician, an artist, giving what he has. (The video of Cash singing the carol is well worth watching.)

How can I not picture the man we know as Johnny Cash into the persona of the drummer boy? For here is Cash, singing first-person about the little drummer boy who had nothing to give but his drum-playing. When Cash sings the line “I played my best for him,” it’s hard not to compress all the songs he sang in all those jails into such passionate, self-giving words. This is the privilege when craftsmanship and faith infuse—they spur each other on, with whatever material we’ve got—paints, words, muscles, pebbles, flour, sound.

But there is a line in “The Little Drummer Boy” that says more about this faith-craft connection. The drummer boy, in the first verse, is called to bring a gift to the king. The second verse starts with the drummer despairing—

Little Baby, pa rum pump um pum I am a poor boy too, pa rum pump um pum I have no gift to bring . . .

I am a poor boy too. When Cash sings this line, he somehow gets the whole meaning of the word poor—not just without coins or trinkets—but poor as in poor in spirit, in need of help and courage and a way forward.

There’s days when I have a kind of zest for the craft work of fiction writing—figuring out a plot, re-tackling a dialogue exchange for the twenty-third time, researching how beeswax candles were made in the fourteenth century. But other times it frightens me how empty my well is. Exhaustion seeps into the edges of the page, turning my words into inky and confused puddles. Ideas feel brittle and old. Why is the story so frayed, my vision so fuzzy? Will I be able to make what I yearn to? What do I really have to give?

After the drummer boy admits his poverty, he picks up his drum and plays. Any craftsmanship I’ve practiced is certainly a gift I can give—but I wonder if I’m wrong to assume I should give from my strengths. What if I were to create from my poverty? What if it’s okay to make, fashion, create, labor, from a place of having very little? I am poor. I am in need. I don’t have the right words or the right story; my opaque heart makes it hard for me to be honest, even on the secret white page. But all this, the blurred edges and scared inadequacies, is part of the gift.

To create from this place of being “a poor boy too”—what else does it yield?

Maybe a gentleness towards ourselves, working as we can in the edges of the day. Maybe a gentleness towards others making what they can, be it poems or children’s lunches, in tiredness and constraint. Perhaps too, to create from a place of lowliness means creating out of a deeper human awareness towards those who feel they have nothing to give. The little drummer boy, empty of a gift, saw that Jesus was poor too, and this gave him courage to play.

This meekness of Jesus at birth curls into the heart of craftsmanship. We can pick up our worn drums and play the best we can, and play whatever we can, under the stable’s low eaves.