Columbo and the Melancholy Dane

Christina Lee

In a chapter of Works of Love entitled “Love Believes All Things –And Yet is Never Deceived,” Kierkegaard describes two levels of love: the lower level, self-love, which seeks out self-affirmation and is easily deceived, and the higher level, the level he tells us we must reach — a love so strong that it wards off all deception.

In a chapter of Works of Love entitled “Love Believes All Things –And Yet is Never Deceived,” Kierkegaard describes two levels of love: the lower level, self-love, which seeks out self-affirmation and is easily deceived, and the higher level, the level he tells us we must reach — a love so strong that it wards off all deception.

I’ve read this chapter many times, but it never quite clicked for me. Until I started binge-watching “Columbo”. God bless Netflix.

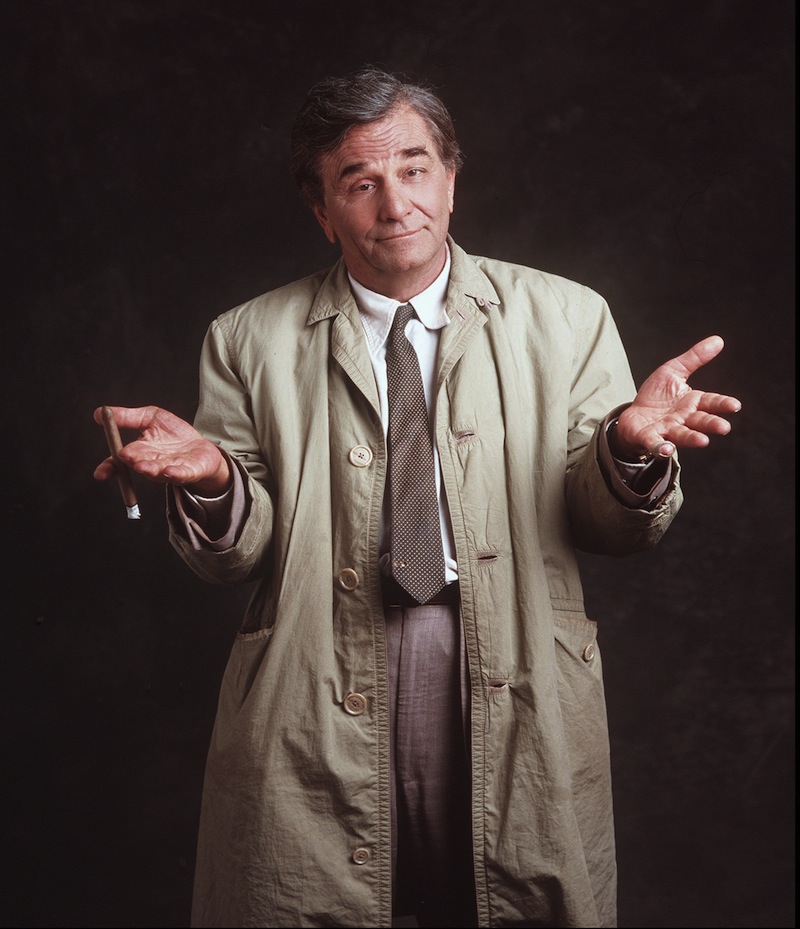

Let me tell you a little about Columbo. First of all, I adore him. At this point, I’ve logged so many hours with the old codger that he seems like a dear uncle. He’s a mess: he drives an old beater, he wears a ratty raincoat, and he never combs his hair. He’s stingy, groveling, and usually hungry. And he always gets his man.

As for the plot of the show, the formula never wavers: a murder is committed in the first few minutes, on-camera. Columbo shows up at the scene of the crime. He slinks through the crowd, often being mistaken for a bum or the help. Soon, he’s sniffed out the murderer — usually a vain, powerful and smooth-talking fellow

As Kierkegaard points out, “Do you know any stronger expression for superiority than this, that the superior one also has the appearance of being the weaker? Consider someone who is infinitely superior to others in understanding, and you will see that he has the appearance of an ordinary person.”

The murderer dismisses Columbo because of his clothes, his shoes, his height, his propensity to bring his dog on assignment or to ramble on about his extended family.

Columbo just doesn’t care. He knows where his self-worth lies — not in their opinion, but in unearthing the truth.

Since we, the audience, have witnessed the crime, we side with Columbo, no matter how he appears to bumble. We’re in on the joke. We understand Kierkegaard when he writes, “True superiority can never be deceived.”

As the plot unfolds, the murderer grows more confident, just as Kierkegaard describes those embroiled in self-love: “The cunning deceiver, who moves with the most supple, most ingratiating flexibility of craftiness — he does not perceive how clumsily he proceeds.”

This is the joy of the show — watching the murderer simmer in his pride. It doesn’t hurt that, since the show is 30 years old, the murder’s “slick” persona is often laughably dated.

Kierkegaard claims that once we view love in the right way, not as a currency to be hoarded and stolen, but “precisely in not requiring reciprocity,” we’re freed of the danger of deception. We’re freed into a love that “believes all things — and is never deceived.”

It is when you have this love, this truth, that appearances stop mattering. Love is no longer a currency, something to steal or sell. It is just there, as solid as truth. A constant. Kierkegaard’s point is that those who can’t see this look as foolish as Columbo’s smooth-talking, designer-bell-bottom-sporting, doomed murderers. Those who get it are freed of all fear of deception and of judgment, freed to don wrinkled raincoats and scuffed shoes and the “courage to endure the world’s judgment that it is so indescribably foolish.”

At the end of the chapter, Kierkegaard admits that reaching this higher understanding of love is really, really hard. Even if we can grasp its goodness, we’ll still approach it like “a dog, which can indeed learn to walk upright but still always prefers to walk on all fours.”

Maybe that’s why Columbo did so well — for an hour a week (or, these days, as many hours as you’ve got to plop in front of your computer) you’re automatically on the right side, lifted to the higher level. The natural temptation to be suckered in by vanity, self-deception, and a well-groomed mustache is gone.

When I first read Works of Love, I interpreted this higher view of love as total detachment. But Columbo actually posits something a bit more complicated.

Columbo is not freed of caring. He’s just freed of caring about the wrong thing. Columbo is obsessed with justice. He doesn’t give a rats-ass about what people think of him. And I think that’s the goal — understanding the nature of love frees us to practice that love.