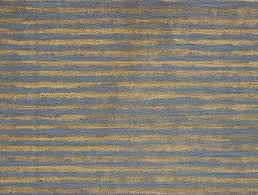

Agnes Martin (1912-2004) painted lines and grids and blocks of color. The exhibit of her work at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, an extensive retrospective spanning the decades of her career, offers visitors a chance to view such simple things as these lines and grids and blocks of color.

Agnes Martin (1912-2004) painted lines and grids and blocks of color. The exhibit of her work at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, an extensive retrospective spanning the decades of her career, offers visitors a chance to view such simple things as these lines and grids and blocks of color.

The exhibit is on the third floor of the Broad Contemporary Art building. It’s spacious there, filtered light from the glass-covered roof filling the space with restrained luminosity. It’s a museum, so it’s a hushed space too, housing silent canvases and quiet spectators.

All of this—the quietness and light and the high ceilings and big white walls—works to present to us these strange, ineffable creations by Agnes Martin. Six by six foot canvases spread out and open before us. There’s The Rain, on which a gray-softly-smeared-with-grey background floats two blocks of mottled, emerging color—the top a dark blue, the bottom a brown-grey taupe. There’s Night Sea, a white grid of fragile, perfect half-inch rectangles over a muted sapphire blue. From her later work is Innocent Living, a gently stacked row of the softest hues in yellow, gray, blue.

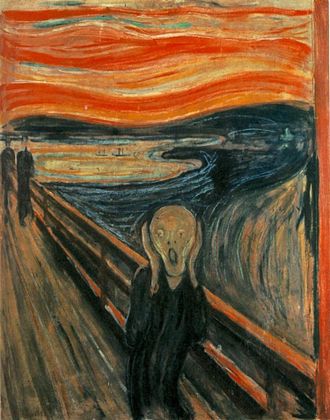

June was a stressful month for me, for many reasons. But in any case, most of us don’t need “reasons” for stress—the rigmarole of upkeep can be exhausting in most seasons. So when I walked onto that third floor, there was a part of me that was frayed, nervous, elsewhere with my to-do’s.

And then, kind of like still ponds or warm pools of light, Agnes Martin’s paintings were waiting. But in using the metaphors of pond and pool, I do a disservice. It is really the paintings’ soft, profound emptiness of form that pours itself out into the viewer. The formlessness rolls across the room in soothing undulations, strange lullabies that catch a restless child off-guard. Martin herself wrote, in her famous poem “The Untroubled Mind”:

These paintings are about freedom from the cares of the world

from worldliness

In her lack of form, in her deeply restrained palette of shape and color, it is as of she unearths deeper spaces for us to enter into. “My paintings have neither object nor space nor line,” she wrote, “nor anything—no forms. They are light, lightness, about merging, about formlessness . . . You wouldn’t think of form by an ocean. You can go in if you don’t encounter anything.”

We enter into the painting, and something is caught, ignited, remembered and recollected. The paintings somehow allow us to present ourselves, in the moment, with all the accumulated moments pooled within us. The grid waits before us like a matrix of inner being, a delicate and endless structure designed for us to hang our moving, wrestling shapes of psyche onto.

The generosity of the grid—of the mind of Agnes Martin—is just that. These pieces have such restraint that they can become spaces for emptying and opening. Marin wrote, “When I first made a grid I happened to be thinking of the innocence of trees and then this grid came into my mind and I thought it represented innocence, and I still do, and so I painted it and then I was satisfied. I thought, this is my vision.”

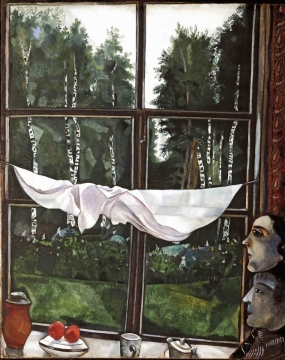

Untitled #3 from 2003 waits for someone to approach it. The top section, a delicate shade of pale dove-wing gray with long, hand-painted lines going down, hovers over the bottom section, a soft, natural brown. The color is reminiscent of sand, wood, dirt, clay. It’s hard not to think of a horizon line. Shore and sky. Or a table in a quiet room, waiting for schoolwork and dinnertime. Or a desert, a long vista to travel, to travail, to mark with footsteps. Or a windowsill, looking out and out and out . . .

It fosters a deep gratitude, the painting does, for the scores of tracts inside of us, that we can meet such seeming emptiness with such rich play and recollection. It isn’t emptiness of course, but the kindness of an artist to make such an open space as it would seem so, one part of a two-way dynamic: the created locale waiting for the human counterpart to perch, enter, and perhaps, be restored.

-

The exhibition Agnes Martin will be at the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art until Sept 11, 2016.

Outside my kitchen window, a gingko tree

bursts gold, fan-shaped leaves shimmering

Outside my kitchen window, a gingko tree

bursts gold, fan-shaped leaves shimmering

I pretty much went back to work. Nothing beats reality.

—

I pretty much went back to work. Nothing beats reality.

—

Naomi Shihab Nye describes poetry as “a conversation with the world, a conversation with those words on the page allowing them to speak back to you—a conversation with yourself.”

Naomi Shihab Nye describes poetry as “a conversation with the world, a conversation with those words on the page allowing them to speak back to you—a conversation with yourself.” Read

Read

![Photo by Sara Reid - Flick [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://static1.squarespace.com/static/5898e29c725e25e7132d5a5a/58aa11bc9656ca13c4524c68/58aa12179656ca13c4525dcd/1487540759619/3599597595_1d64cae554_z.jpg?format=original)

“Exile brings you overnight where it would normally take a lifetime to go.”

“Exile brings you overnight where it would normally take a lifetime to go.”

![Photo by Sara Reid - Flick [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://static1.squarespace.com/static/5898e29c725e25e7132d5a5a/58aa11bc9656ca13c4524c68/58aa12169656ca13c4525db8/1487540758260/tv.jpg?format=original)

![By Masao Nakagami [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5898e29c725e25e7132d5a5a/1508808035105-2RO1L6V7MSY94EEGYLTE/Early_White_Stripes.jpg)

Feel it—but remember, millennia have felt it—

the sea and the beasts and the mindless stars

wrestle it down today as ever—

—

Feel it—but remember, millennia have felt it—

the sea and the beasts and the mindless stars

wrestle it down today as ever—

—