I’m a Recovering Church Dramatist

Paul Luikart

I’m a recovering church dramatist. Back in the day, I worked with a performance team. We wrote sketches and performed them during Sunday services. We had a lot of fun and we were, dare I brag, pretty funny. This was in Chicago where improv is king. We'd craft scripted sketches out of improvised scenes we made up related to the pastors’ sermon topics. It was fairly organic at first and, for the most part, we had the freedom to do whatever we wanted. As long as we didn’t swear or anything.

I’m a recovering church dramatist. Back in the day, I worked with a performance team. We wrote sketches and performed them during Sunday services. We had a lot of fun and we were, dare I brag, pretty funny. This was in Chicago where improv is king. We'd craft scripted sketches out of improvised scenes we made up related to the pastors’ sermon topics. It was fairly organic at first and, for the most part, we had the freedom to do whatever we wanted. As long as we didn’t swear or anything.

I was proud of what we created back then, but as I reflect on those sketches now, there’s a bit of a dark, nagging undertone that I’m not sure I noticed at the time. It’s not that what we did was bad, but it never could have stood alone. What we produced was inextricably linked to those sermons, subserviently linked in fact, and in the big picture, subserviently linked to the evangelical purposes of either a) saving souls or b) edifying saved souls. Art, if you can call what we did art, was a serf to the vassal of the modern evangelical church.

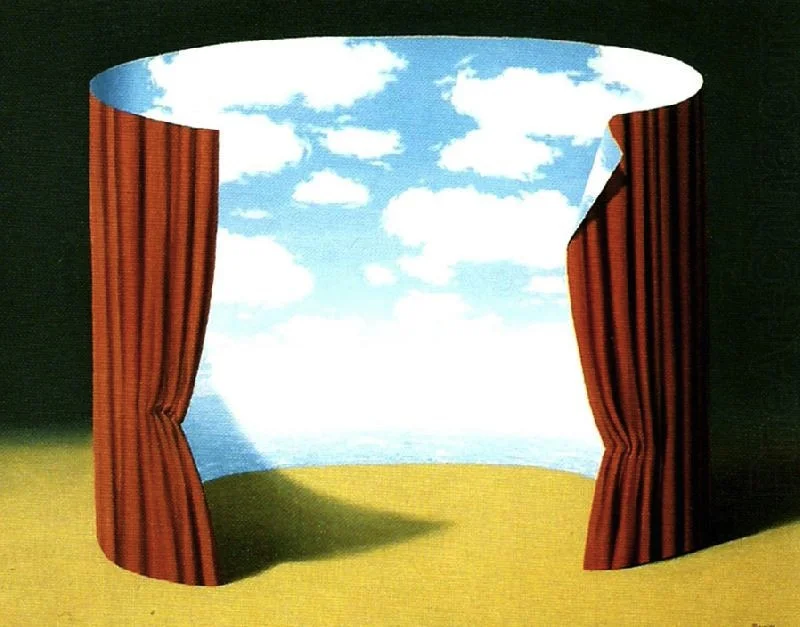

A be-all-end-all definition of art is difficult to come across, but one thing I'm certain of is that art is not a slave. Roping art to a cause of some kind is a misuse of it, one that demonstrates a core misunderstanding of the stuff. But stating what art isn’t begs the question, "What is it?" Ha. You might just as well ask, "Who is God?" especially if you're up for some maddening non-answers. There are some pat answers—"Art is human expression," "God is love"—that aren't necessarily false. It's just that they can only ever be partially true.

Art is inherently mysterious. I think the typical human response to the grandly mysterious (like art, like God) is a knee-jerk, semi-conscious attempt at appropriation. If we can’t fully describe something, we yank it from its own empire and compress it to grasp-able suburban terms, not realizing that as we compress it, we shear it of its essence, the thing that makes the thing the thing. Art is no longer art, but propaganda, and propaganda harangues with one of two choices: Are you with us or are you against us? Your life teeters on your answer. Answer now.

Art, like God, permits an infinite number of responses to itself. It piques curiosity, provokes introspection, picks at our core values, and invites us to return over and over again. Those who patronize the arts correctly remove their crowns and listen. Those who patronize incorrectly first seek themselves in the painting, the novel, the symphony, and give up on art all together when, in fact, they find themselves.

The leadership at my church back then eventually chopped our sketches from the services permanently. I never knew why exactly. We didn’t swear, not even once. Probably because first they made us quit writing our own stuff and use Willow Creek Community Church’s pre-written stuff. But whatever the reason, it was for the best. Though we were ultimately mistreating art, it never shunned us. Art, like God, was kind to us.