Acts of Concentration

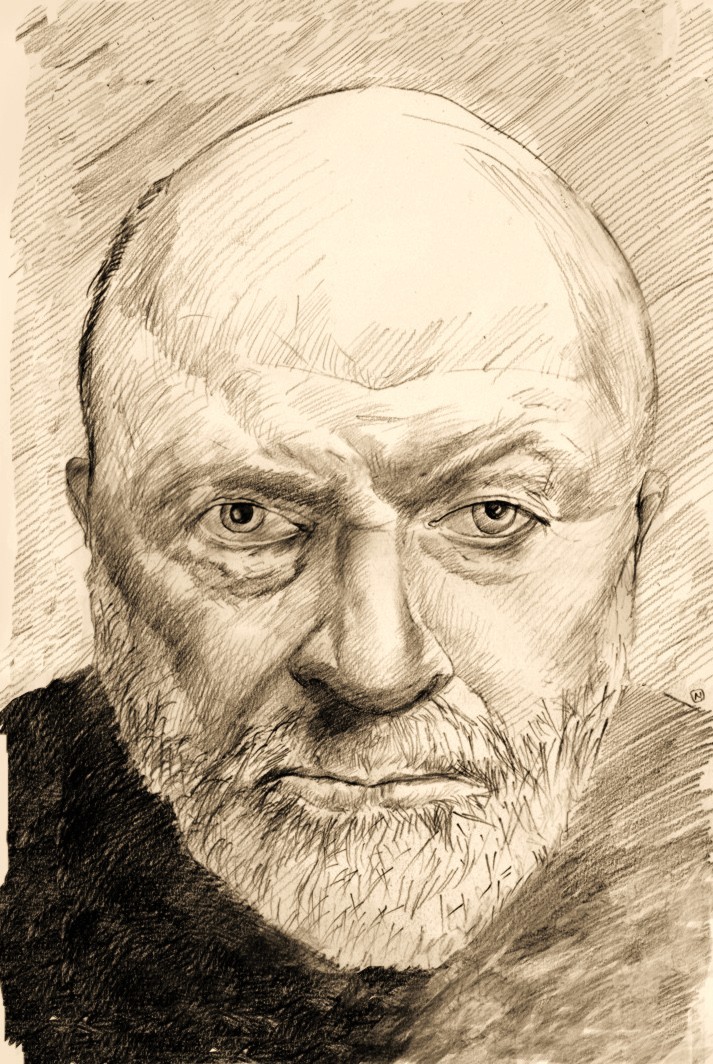

William Coleman

When Geoffrey Hill died at the end of June, a friend and I were in the midst of trying to break into the agate of one of his poems. Back and forth, over the span of days, we emailed etymologies and conjectures, trying to work our way into bright allusive seams and necessary recesses where meanings crystallized.

When Geoffrey Hill died at the end of June, a friend and I were in the midst of trying to break into the agate of one of his poems. Back and forth, over the span of days, we emailed etymologies and conjectures, trying to work our way into bright allusive seams and necessary recesses where meanings crystallized.

In a word, Geoffrey Hill wrote work that's fraught. But as I can begin to attest, the sense of vitality that comes of arduously attending to Hill's work is profound. It's akin to the extension of consciousness William James describes in an essay on the state we call mystical. The expanse of awareness, he writes, is like seeing an expanse of shore "at the ebb of a spring tide." Hidden forms of life and history that lend the constant sea its shape and character are suddenly, and at once, utterly visible. Reading Hill is to enter such a state, but (at least for me) slowly, as gradually as light raises water.

To be sure, Geoffrey Hill could be--what is the word?--bombastic in public. I once heard a recording of him introducing a poem: "You don't ENJOY poetry!" His voice pounded the air as his hand pounded the podium (the sound was unmistakable). "You try to enjoy a poem and the poem says, 'BUGGER OFF!'"

But bombastic, of course, is precisely not the word, a fact I could have obtained through the the execution of the merest of modern efforts: highlighting, right-clicking, choosing "look up 'bombastic.'" The fact that I did not do so, but instead carelessly relied upon some vague notion of aggressive intensity I imbibed from some source I cannot name, is one of the very issues Hill's work is inclined to rectify.

As he told an interviewer last April, "Our contemporary ignorance results from methods of communication and education which have destroyed memory and dissipated attention."

Bombast once referred to cotton wadding: it was used to inflate the finery of the vainly rich. By Shakespeare's day, one's speech could be described as thus inflated, regardless of one's wealth: to speak with bombast was (and is) to speak in order to seem, to speak pompously, vacuously. Imagine saying seriously of Geoffrey Hill that his words are empty, or composed to puff himself up.

Words change, to be sure. But to regard such change—and language itself—as passively as one might absorb a slogan, with no specific thought as to resonance or history, no felt sense of perspective, no exacting efforts of attention that serve to alienate just enough to ensure a measure of freedom, is to lose both private self and public history. It is to lose what makes us human.

Hill insisted on setting things right, word by word. Even if those words are not yet understood by me, even if some of what's right is incomprehensible and may remain so for the rest of my life, Hill's concentrated efforts evoke a desire in me to be so concentrated, and a belief that such concentration matters.