A Poet in Pursuit of Freedom

Jessica Brown

George Moses Horton wrote poems, and for a very long time he attempted to sell these poems to purchase his freedom from slavery.

Read MoreUse the form on the right to contact us.

You can edit the text in this area, and change where the contact form on the right submits to, by entering edit mode using the modes on the bottom right.

123 Street Avenue, City Town, 99999

(123) 555-6789

email@address.com

You can set your address, phone number, email and site description in the settings tab.

Link to read me page with more information.

Filtering by Tag: Paradise Lost

George Moses Horton wrote poems, and for a very long time he attempted to sell these poems to purchase his freedom from slavery.

Read More Last night I dreamt that I got lost again. It’s a frequent dream for me: I can’t find my car or my way home. While that type of dream may have metaphorical meaning for some people, I think it is most likely pretty literal for me. When I was a kid, sometimes I had to ask my friends at sleepovers to remind me where their bathroom was because I couldn’t quite remember their house layout and I was scared of opening the wrong door. Before smart phones and GPSs, using public transit was a complete nightmare. In addition to having the tendency of getting lost, I am also pretty good at remaining unseen. It was not that uncommon for me to be the last one sitting on the bus patiently awaiting my destination when the driver would turn around, and, with a start say, “I had no idea there was still a passenger on here!” Sometimes, I had gotten on the right bus, but on the wrong side of the street and so ended up at the other side of the city.

Last night I dreamt that I got lost again. It’s a frequent dream for me: I can’t find my car or my way home. While that type of dream may have metaphorical meaning for some people, I think it is most likely pretty literal for me. When I was a kid, sometimes I had to ask my friends at sleepovers to remind me where their bathroom was because I couldn’t quite remember their house layout and I was scared of opening the wrong door. Before smart phones and GPSs, using public transit was a complete nightmare. In addition to having the tendency of getting lost, I am also pretty good at remaining unseen. It was not that uncommon for me to be the last one sitting on the bus patiently awaiting my destination when the driver would turn around, and, with a start say, “I had no idea there was still a passenger on here!” Sometimes, I had gotten on the right bus, but on the wrong side of the street and so ended up at the other side of the city.

Often, in an attempt to make me feel better, people will tell me that they are not very good with directions either. They mean well, but it doesn’t really help; it makes me feel like they think they understand, but they don’t. It can be somewhat isolating. So, when I meet someone who has a similar challenge it can be really quite bonding.

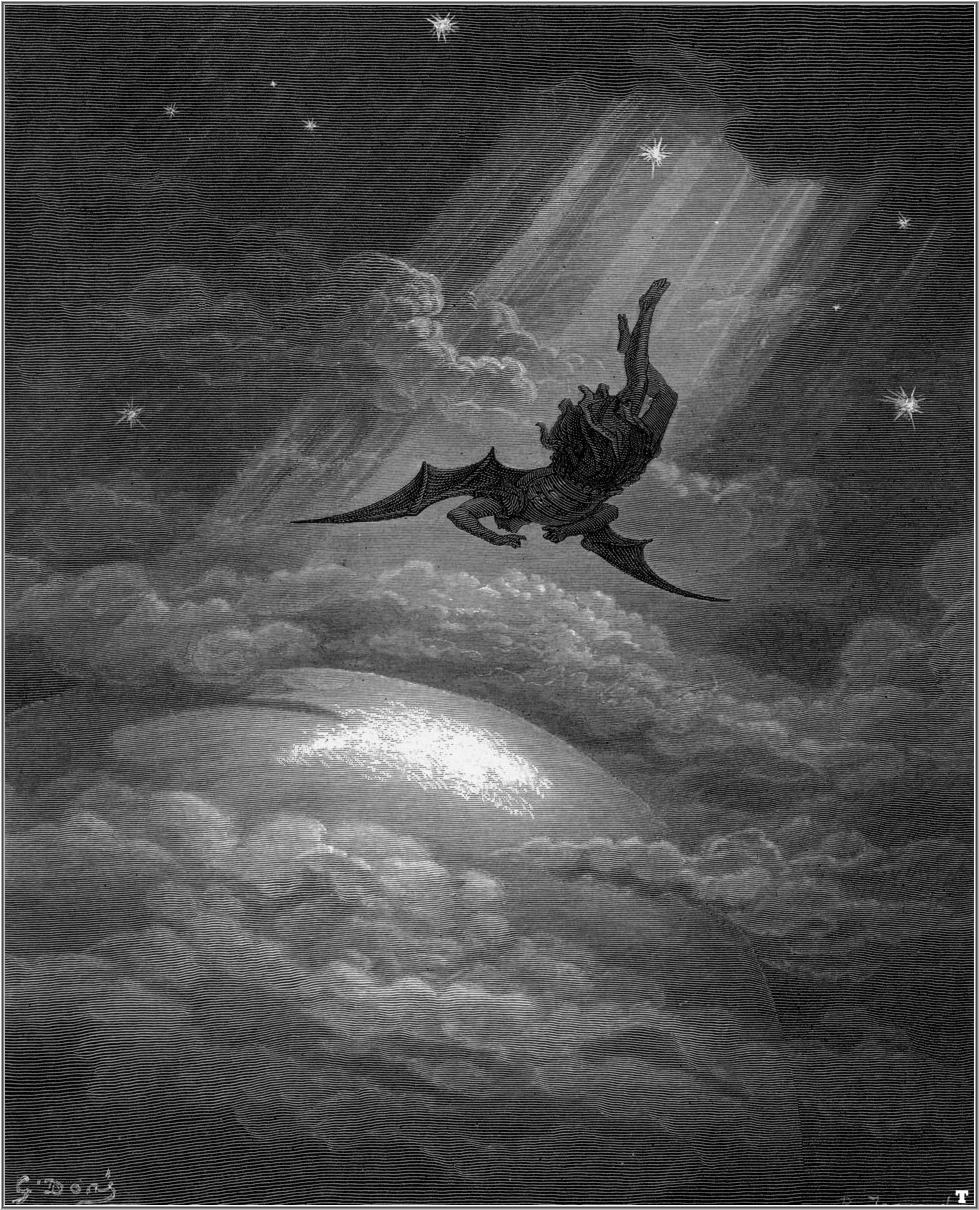

The petite elderly professor who taught me Paradise Lost was like that. One of her colleagues once told our class that said professor was so perpetually lost that it was sometimes an accomplishment for her to find her way home from a neighbour’s. True or not, the impression stuck and she became among my favorite instructors. When she spoke of Milton’s Satan, Adam, and Eve, I paid attention and was quite nearly riveted. Without power point, whiteboard, props or even a dramatic voice, the passages she pointed to were gripping. I still read it from time to time. The story fascinates me. I know the ending, how can I possibly be so transfixed, I sometimes wonder. I’m beginning to think I might have an inkling of what particularly fascinates me about the story: Satan.

Perhaps of all the lines in Paradise Lost, the description of Satan’s “stubborn patience as with triple steel” is among the most chilling for me. The Fallen Angel’s designs to deceive and destroy God’s freshly created Eve and Adam stuns me with its icy resolution. It strikes me because of its dissimilarity with the nature of evil that I often see portrayed in culture and literature: hot, passionate, sensual desire with searing results. Milton, however, shows us a Satan who is not sexy, only stubborn.

Like Francis Underwood of House of Cards, Satan’s plans are strategic, stealthy and unwearied: his will is enduring and his resilience indestructible. Perhaps this image is so striking for me because of the composed calmness the line suggests he possesses. There is little hustle and bustle going on at this moment; instead, there is cold calculation. Rather than the perpetrator of forbidden fun like the devil (who can forget Al Pacino in this role) in Devil’s Advocate, Milton’s antagonist embodies the nature of evil Charles Williams explores in Descent into Hell: deliberate, incremental and isolating steps that go deeper and deeper into the non-spectacular: the anti-spectacular, in fact, for it is oblivion.

“Boring,” “boorish,” and (my personal favorite) “profoundly terrible” are some of the nicer descriptors that can be found in the reviews of the Wachowski siblings’ latest movie. At just over two hours, this space-opera-cum-heroic-fantasy is acknowledged as visually appealing with its impressive special effects, but declared decidedly drab in the plot department. Worse than merely drab, however, some of the more literary minded commenters pronounce Jupiter, the main character, as nauseatingly implausible. Now, while I do agree with them that Jupiter is most definitely not a classical hero, I wonder at our underlying assumptions of heroism that leave some of us with the feeling that Jupiter got the crap side of the stick in this movie.

If you haven’t seen it, here’s a brutishly rudimentary plot summary (spoiler warning). Jupiter, the female protagonist, is a young, overworked, under-appreciated, and unfulfilled maid in Chicago. Trapped in a life of scrubbing toilets and cleaning up other people’s trash, she starts and ends each day in exhaustion. Jupiter lives in extremely tight quarters with her Russian immigrant mother and extended family, which gives her little personal space or room for expression: the theme constantly upon her lips before her big adventure is, “I hate my life.” Pressured by a capitalistic cousin into selling her eggs at a fertility clinic, she is nearly abducted by assassin aliens and soon thrust into an interplanetary journey where she learns she is actually Earth’s royal owner. Assisted throughout the adventure (and rescued again and again … and again ... and then some) by a genetically altered ex-soldier with flying boots, she is kidnapped, conned, and beat up by royal alien siblings intent on harvesting Earth’s population into a vitality serum: a practice they have been doing on other planets for thousands of years. Always rescued at the last minute by flying boot boy, the aliens are thwarted, the earth remains blissfully ignorant of and safe from the villains and Jupiter lives to see another day. The movie ends with her sacrificing sleep to cheerfully prepare breakfast for the relatives, taking up her cleaning job, and going on flying adventures with her new boyfriend (flying boot boy) and his now-returned sexy set of wings.

“Boring,” “boorish,” and (my personal favorite) “profoundly terrible” are some of the nicer descriptors that can be found in the reviews of the Wachowski siblings’ latest movie. At just over two hours, this space-opera-cum-heroic-fantasy is acknowledged as visually appealing with its impressive special effects, but declared decidedly drab in the plot department. Worse than merely drab, however, some of the more literary minded commenters pronounce Jupiter, the main character, as nauseatingly implausible. Now, while I do agree with them that Jupiter is most definitely not a classical hero, I wonder at our underlying assumptions of heroism that leave some of us with the feeling that Jupiter got the crap side of the stick in this movie.

If you haven’t seen it, here’s a brutishly rudimentary plot summary (spoiler warning). Jupiter, the female protagonist, is a young, overworked, under-appreciated, and unfulfilled maid in Chicago. Trapped in a life of scrubbing toilets and cleaning up other people’s trash, she starts and ends each day in exhaustion. Jupiter lives in extremely tight quarters with her Russian immigrant mother and extended family, which gives her little personal space or room for expression: the theme constantly upon her lips before her big adventure is, “I hate my life.” Pressured by a capitalistic cousin into selling her eggs at a fertility clinic, she is nearly abducted by assassin aliens and soon thrust into an interplanetary journey where she learns she is actually Earth’s royal owner. Assisted throughout the adventure (and rescued again and again … and again ... and then some) by a genetically altered ex-soldier with flying boots, she is kidnapped, conned, and beat up by royal alien siblings intent on harvesting Earth’s population into a vitality serum: a practice they have been doing on other planets for thousands of years. Always rescued at the last minute by flying boot boy, the aliens are thwarted, the earth remains blissfully ignorant of and safe from the villains and Jupiter lives to see another day. The movie ends with her sacrificing sleep to cheerfully prepare breakfast for the relatives, taking up her cleaning job, and going on flying adventures with her new boyfriend (flying boot boy) and his now-returned sexy set of wings.

Okay—my apologies to anyone who has seen the movie and can readily identify the 27 important plot points that I have casually omitted. But, I trust the theme is clear: little Miss Royalty is rescued (a lot), is not particularly ambitious, seems perfectly content to return to an unimportant job and crowded house, and never seeks out public recognition. Oddly enough, it seems somewhere along the journey she internalizes a new axiom: “It’s not about what I do, it’s about who I am."

As you’ve no doubt gathered, this is not your typical hero story. But what is a hero story, and what makes it so?

For those who’ve read Paradise Lost (a 17thcentury epic poem that dramatizes the creation and subsequent eviction of Eve and Adam from the garden. Satan and his super sneaky schemes to destroy the happy couple and amass an army to usurp God’s Kingship also play a prominent role in the plot) in class, or are generally familiar with the story, we were taught according to two schools of thought. One, Milton screwed up and made Satan the show-stealing character by accident. According to this ideology, Satan is actually the hero of the story. Strong, cunning, ambitious, independent, and a natural-born leader: Satan is clearly the classical hero whom Milton himself unwittingly valorizes. Paradise Lost, then, becomes a tragedy because our favorite guy, Satan, loses.

The other school of thought suggests that in Satan’s unquenchable thirst for status (he wants to be ruler of the world), we uncomfortably identify our own fallen and destructive lust for prestige. Educators of this persuasion suggest that in Satan’s defiant pursuit of dominion, Milton demonstrates the seductive dangers of the quest for control. This second school of thought is a less popular one because in Paradise Lost, Satan is such a sympathetic character; and, indeed while we may not overtly root for him, our culture often tells us that complete self-sufficiency is the key ingredient of happiness. Satan, according to our society’s mores, is a heroic figure. The question then becomes a matter of identifying our current model of heroism.

Which brings me back to Jupiter Ascending. Much of the angst at the film is directed at its improbable plot and boring main character. What kind of story stars a hero who goes on a journey to learn s/he is really, really important (and has a whole lot of resources at her/his disposal) and then moves back to an inhospitable and banal homeland, bickering neighbors, takes up a menial job, and smiles about living the daily grind, saying “it’s not what I do, it’s who I am that matters”? Not a contemporary hero.

Culture often tells us that as heroes of our own stories, we must have status in order to experience personal fulfillment. We have been told that we need resources to experience the world and get the recognition we crave. In other words, we have been told that to be successful is to wield power; and, perhaps even more importantly, be recognized for that power.

I wonder if it’s possible that some of our dissatisfaction with Jupiter’s choices mirror our own consumption of a toxic cultural narrative: a narrative that says, it’s never about who you are, it’s only about what you do. A narrative that uncomfortably sides with Satan's quest in that old tale of so much discussion.

The journey began as many tandem road trips in the modern world do, with two husbands behind the wheel of their respective vehicles and each wife beside him texting back and forth and pinning images to Pinterest. At a roadside Starbucks near Austin, the configuration changed. My wife Laurie and Mike’s wife Lisa hopped in my station wagon, freeing me to sit in the passenger seat of Mike’s rental car with a paperback edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost, which I started reading aloud. Bumper stickers in the Texas capitol encourage passersby to “Keep Austin Weird.” That January afternoon, we did our part.

Mike would be teaching Books 1 and 2 to a group of thirty-odd students the next morning, and while he’d taught the poem before, a refresher never hurts. For me this was the first reading since a hasty grad school skim. Paradise Lost is much better than I remember. For one thing, I actually follow most of his references. (Half of them, anyway.) All my reading life was preparation, it seems. I’ve been training for Milton the way runners train for a marathon.

Milton is bold. Virgil appropriated Greek culture for The Aeneid, and Milton does likewise, claiming the whole of the classical world for his epic––only in place of Odysseus or Aeneas he casts none other than Satan, that bad eminence, and treats him very much like a hero. Book 2’s council in Pandaemonium, the city of devils, is straight out of Homer––or perhaps Tolkein, ending as it does with Satan embarking on a quest none of his peers have the courage to undertake. (When we reach that part of the story, I actually substitute Frodo’s words for Milton’s: “I will take the ring, though I do not know the way.” It works.) This sleight-of-hero calls into question so many ideas that resonate: The desire to be free, to be captain of our souls, to rule rather than serve, and to make a name for ourselves. These are noble virtues, but coming from Lucifer, you have to wonder.

The next morning in class the story of our drive-time reading comes out. The students are embarrassed for us. They worry, too, that this pair of middle aged men is a warning: continue down the path of literature, and this is what you will become, a declaimer of verse, out loud and unashamed.

Somewhere toward the end of the class discussion, Mike puts me on the spot. Do I have any thoughts to share? “Maybe Milton is giving us a reason to ask whether the things we admire most,” I say, “are a testament to the fact that something’s gone wrong with us.” The story of the fall, in other words, is written in the tales not just of our sinners, but of our heroes.

And then I tell them to read next week’s assignment out loud the way blind Milton intended. They look back at me, doubtful. Twenty years from now they’ll understand.

(Art by William Blake, Satan Addressing His Potentates)