Questions or Booking Travel?

Tom Sturch

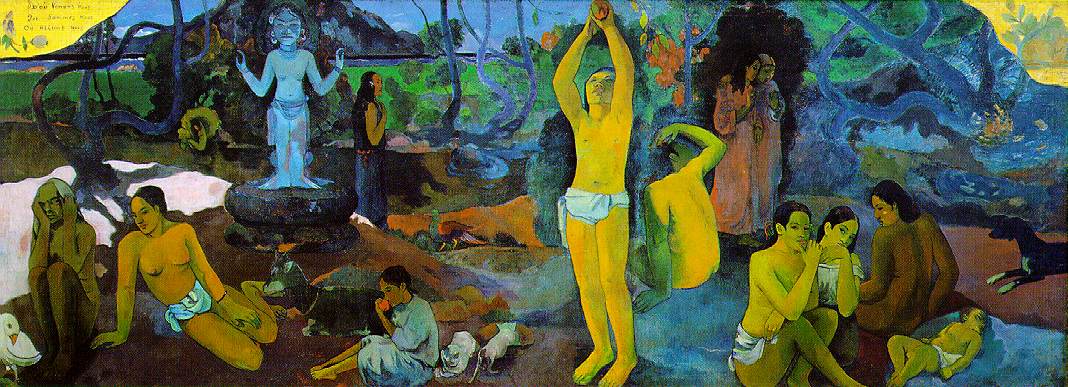

Now through June 8 MoMA is exhibiting about 150 works of Paul Gauguin. On MoMA's event website is a handy map and chronology of his life and work. The time line leads to a moment when in 1895, forty-five year-old Paul Gauguin traveled to Tahiti, leaving his wife and five children behind forever. Native of France, he grew up in Peru, sailed the world with the merchant marine, and worked for years in the French stock exchange. In 1879 he began to paint and exhibit with the Impressionists. When France's economy collapsed his business failed and after that painted full time. He became intrigued with Rousseau’s theories of the Natural Human and experimented widely with artistic materials and forms. In Tahiti he painted his masterpiece, "Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?” The title, as you can just see in the link, is written in the upper left hand corner of the painting.

Suppose Gauguin painted today. The context is fairly similar: poor economy, debts and responsibilities, and a nagging sense we were made for more than this. Of course Tahiti today would feature fewer natives and better hotels. And I think his three questions would probably morph into our texting shorthand, WTF? Interestingly, Gauguin didn't use question marks in the painting title. His “questions” are rendered as statements– statements of the existential angst that he reported feeling to the point of attempting suicide after finishing the work. Likewise, our WTF is usually rendered, not as a question, but a malediction. It is intended as a judgment, a confession of helplessness and tacit defeat. It separates us from the world, and more insidiously, it becomes a ticket to pursue life as we please – a self indulgence that books travel to our imaginary lives that lie outside the reality of suffering.

While I write this my neighborhood is a cacophony of leaf blowers and my cat keeps pawing my arm. I have a boatload of work to do, bills to pay and time bears down. Forget war and poverty. What good are these few words? Am I mocked? Maybe so, but I have a choice in how I will respond. I can manifest an impossible version of life and escape to a convenient “Tahiti”, or I can speak into the chaos, join with others and help make a new world of this one.

One day soon we'll hear the shorthand curse again. Suppose instead of giving it form we affirm that life is hard, that suffering is a common bond, and then re-imagine our goals? What if we begin to answer the big questions a little at a time? What if instead of checking out we keep watch for those on the rocks and come alongside? In doing so, might we be transformed from cursing sailors to traveling agents of peace?