The Shape Among the Figures

William Coleman

Poems move us through space of one kind or another. Since so many words began their lives in some action or image (the Latin source of “redundant,” for example, contains the image of overflowing waves), even abstract poetry creates a sense of navigation. In poetry filled with overtly concrete imagery, of course, this movement’s easier to feel, and the shapes described in the movement through the space can be revealing.

Consider these two poems, one by the late Seamus Heaney, an Irishman who taught in America, the other by the late Galway Kinnell, the American son of an Irish immigrant. A dozen years separated their births, and a decade divided the writing of these poems: Heaney’s “Digging” appeared in 1966; Kinnell’s “St. Francis and the Sow” in 1976. In both poems, the shape the speaker’s attention makes—determined by the sequence of imagery in space—describes a figure central to the meaning of the poem.

Heaney’s poem “Digging” begins as an elegy for the life he cannot lead—the farmer’s way of his father and his father’s father—then becomes the very means of uncovering a sense of kinship between that way and his own, a knowledge that gives his life meaning and purpose. As he makes this discovery, his attention drops and rises, dips and returns. It falls from his window to the ground, where it unearths the sustenance he needs: a precisely felt awareness of his place, his people, his history. The fruit of his attention he carries back up to his room, where the gripped pen readies to fall again and again to the work at hand. Digging.

Digging

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.

Under my window, a clean rasping sound

When the spade sinks into gravelly ground:

My father, digging. I look down

Till his straining rump among the flowerbeds

Bends low, comes up twenty years away

Stooping in rhythm through potato drills

Where he was digging.

The coarse boot nestled on the lug, the shaft

Against the inside knee was levered firmly.

He rooted out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep

To scatter new potatoes that we picked,

Loving their cool hardness in our hands.

By God, the old man could handle a spade.

Just like his old man.

My grandfather cut more turf in a day

Than any other man on Toner’s bog.

Once I carried him milk in a bottle

Corked sloppily with paper. He straightened up

To drink it, then fell to right away

Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods

Over his shoulder, going down and down

For the good turf. Digging.

The cold smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap

Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge

Through living roots awaken in my head.

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests. I’ll dig with it.

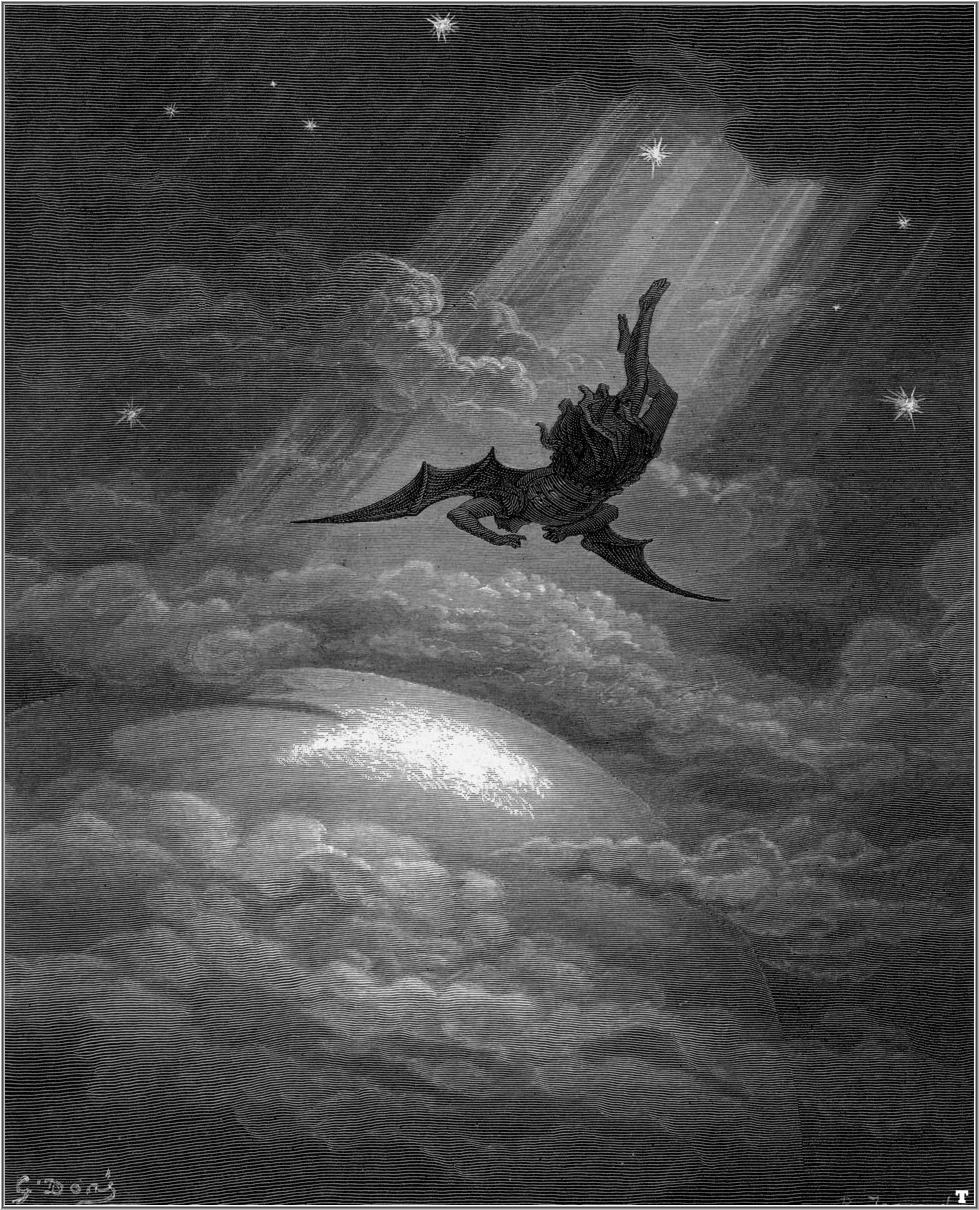

“St. Francis and The Sow” is a song sung in praise of the flesh, especially that which might be called filthy, ugly, broken, stained, beneath the notice of the upright. St. Francis loved each creature equally. He found the imprint of God’s love within every made thing. And so it is no surprise to find the figure of the cross embedded in the description of the animal at the end of the poem, when the speaker leads us in a litany of imagery, from the snout to the tail, then from “the hard spininess spiked out from the spine” down to the “fourteen teats” that nourish the animal’s young. Unmixed attention is prayer, Simone Weil once wrote. Here, our attention to the least among us traces a cross inherent in living flesh, even as our attention’s direction describes the action of a blessing.

Saint Francis and the Sow

The bud

stands for all things,

even for those things that don’t flower,

for everything flowers, from within, of self-blessing;

though sometimes it is necessary

to reteach a thing its loveliness,

to put a hand on its brow

of the flower

and retell it in words and in touch

it is lovely

until it flowers again from within, of self-blessing;

as Saint Francis

put his hand on the creased forehead

of the sow, and told her in words and in touch

blessings of earth on the sow, and the sow

began remembering all down her thick length,

from the earthen snout all the way

through the fodder and slops to the spiritual curl of the tail,

from the hard spininess spiked out from the spine

down through the great broken heart

to the sheer blue milken dreaminess spurting and shuddering

from the fourteen teats into the fourteen mouths sucking and blowing beneath them:

the long, perfect loveliness of sow.

Naomi Shihab Nye describes poetry as “a conversation with the world, a conversation with those words on the page allowing them to speak back to you—a conversation with yourself.”

Naomi Shihab Nye describes poetry as “a conversation with the world, a conversation with those words on the page allowing them to speak back to you—a conversation with yourself.”

"Knowing is the responsible human struggle to rely on clues to focus on a coherent pattern and submit to its reality."

"Knowing is the responsible human struggle to rely on clues to focus on a coherent pattern and submit to its reality."  It’s hard writing about the salty Gulf Coast without the taste of fried biscuits in Mendenhall, Mississippi, or the hypnotic curves of rice paddies in southeast Arkansas, the lonely cotton gins and weathered Baptist churches that survive calamitous storms year after year. Before we can throw our bodies into the roiling sea, there’s a rite of passage we must traverse. It takes nine-and-a-half hours to drive from Little Rock to Orange Beach. Nine-and-a-half hours of poverty and the whims of commodity crop economics. It used to be cotton and rice. Now it’s GMO corn and soy. “You can’t even eat that corn,” my mom would say. A black cloud of starlings shoots past us. “I know, it all goes to the cows outside Denver,” I would reply. Dollar General replaced the mom-and-pop small town shops, and now even those soul-starved places are empty, only to be filled by storefront churches promising salvation by the highway. One sign reads Just Church. Fast food wrappers skitter along asphalt and half-smashed snakes. Upturned armadillos try to hold up the sky with their stubby legs. Meanwhile, kudzu swallows up longleaf pines and the lives that depend on them, and the forest turns into a tomb, encased by this foreign, medicinal vine only Agent Orange could knock out. The roadside greenbelt looks more like a freak show displaying storybook monsters frozen in time – their movements, their joys, their battles all swallowed up by this relentless vine. I don’t care how medicinal it is and what the rumors are for curing cancer. That vine is killing the forests.

It’s hard writing about the salty Gulf Coast without the taste of fried biscuits in Mendenhall, Mississippi, or the hypnotic curves of rice paddies in southeast Arkansas, the lonely cotton gins and weathered Baptist churches that survive calamitous storms year after year. Before we can throw our bodies into the roiling sea, there’s a rite of passage we must traverse. It takes nine-and-a-half hours to drive from Little Rock to Orange Beach. Nine-and-a-half hours of poverty and the whims of commodity crop economics. It used to be cotton and rice. Now it’s GMO corn and soy. “You can’t even eat that corn,” my mom would say. A black cloud of starlings shoots past us. “I know, it all goes to the cows outside Denver,” I would reply. Dollar General replaced the mom-and-pop small town shops, and now even those soul-starved places are empty, only to be filled by storefront churches promising salvation by the highway. One sign reads Just Church. Fast food wrappers skitter along asphalt and half-smashed snakes. Upturned armadillos try to hold up the sky with their stubby legs. Meanwhile, kudzu swallows up longleaf pines and the lives that depend on them, and the forest turns into a tomb, encased by this foreign, medicinal vine only Agent Orange could knock out. The roadside greenbelt looks more like a freak show displaying storybook monsters frozen in time – their movements, their joys, their battles all swallowed up by this relentless vine. I don’t care how medicinal it is and what the rumors are for curing cancer. That vine is killing the forests. Read

Read  Last night I dreamt that I got lost again. It’s a frequent dream for me: I can’t find my car or my way home. While that type of dream may have metaphorical meaning for some people, I think it is most likely pretty literal for me. When I was a kid, sometimes I had to ask my friends at sleepovers to remind me where their bathroom was because I couldn’t quite remember their house layout and I was scared of opening the wrong door. Before smart phones and GPSs, using public transit was a complete nightmare. In addition to having the tendency of getting lost, I am also pretty good at remaining unseen. It was not that uncommon for me to be the last one sitting on the bus patiently awaiting my destination when the driver would turn around, and, with a start say, “I had no idea there was still a passenger on here!” Sometimes, I had gotten on the right bus, but on the wrong side of the street and so ended up at the other side of the city.

Last night I dreamt that I got lost again. It’s a frequent dream for me: I can’t find my car or my way home. While that type of dream may have metaphorical meaning for some people, I think it is most likely pretty literal for me. When I was a kid, sometimes I had to ask my friends at sleepovers to remind me where their bathroom was because I couldn’t quite remember their house layout and I was scared of opening the wrong door. Before smart phones and GPSs, using public transit was a complete nightmare. In addition to having the tendency of getting lost, I am also pretty good at remaining unseen. It was not that uncommon for me to be the last one sitting on the bus patiently awaiting my destination when the driver would turn around, and, with a start say, “I had no idea there was still a passenger on here!” Sometimes, I had gotten on the right bus, but on the wrong side of the street and so ended up at the other side of the city. This fall, I plan to take my twelve-year old pheasant hunting for the first time, as my father took me. Last fall, when he was eleven, I took Micah out to shoot in a gravel pit outside of town, after which time I had one question:

This fall, I plan to take my twelve-year old pheasant hunting for the first time, as my father took me. Last fall, when he was eleven, I took Micah out to shoot in a gravel pit outside of town, after which time I had one question:

Sometimes, when I’m burnt out, I look to Rilke. Not his

Sometimes, when I’m burnt out, I look to Rilke. Not his

The documents are in folders, carefully taken out and laid upon my desk. Others have been folded and refolded; the creases have become a part of the paper. They are birth and marriage and death certificates, transcripts and diplomas. I scan the documents and send the file to one of my translators. After a few hours or days, the translated words in English are sent back. I look through, edit and check. The documents are filled with words like certify, signature, official, issued, expire; it’s pretty straightforward stuff.

The documents are in folders, carefully taken out and laid upon my desk. Others have been folded and refolded; the creases have become a part of the paper. They are birth and marriage and death certificates, transcripts and diplomas. I scan the documents and send the file to one of my translators. After a few hours or days, the translated words in English are sent back. I look through, edit and check. The documents are filled with words like certify, signature, official, issued, expire; it’s pretty straightforward stuff.  As holidays with my extended family arrive, so does the expectation of playing games. Whether in a pool, in the snow, in a gym, on the floor of a living room, or, especially, at the table. Ah! The evening table game. We’ve played everything from “Awkward Family Photos” to “Risk” to “Tenzi” to “Reverse Charades” to the incredible, mind-bending card game “Killer Bunnies”.

As holidays with my extended family arrive, so does the expectation of playing games. Whether in a pool, in the snow, in a gym, on the floor of a living room, or, especially, at the table. Ah! The evening table game. We’ve played everything from “Awkward Family Photos” to “Risk” to “Tenzi” to “Reverse Charades” to the incredible, mind-bending card game “Killer Bunnies”.

The grammarian

The grammarian

Once our boys left home Bev and I were thrust into quick adjustments akin to riders just off the tilt-a whirl. Our stable orbits missed the gravity of their presence. The momentum of parenting doesn't go away once you've spun your progeny off and into the world. So we rotated and balanced the tires, refurnished repainted rooms, re-sized the recipes and learned new steps.

Once our boys left home Bev and I were thrust into quick adjustments akin to riders just off the tilt-a whirl. Our stable orbits missed the gravity of their presence. The momentum of parenting doesn't go away once you've spun your progeny off and into the world. So we rotated and balanced the tires, refurnished repainted rooms, re-sized the recipes and learned new steps.

“I held on to Ginnie Hempstock. She smelled like a farm and like a kitchen, like animals and like food. She smelled very real, and the realness was what I needed at that moment.”

–Neil Gaiman,

“I held on to Ginnie Hempstock. She smelled like a farm and like a kitchen, like animals and like food. She smelled very real, and the realness was what I needed at that moment.”

–Neil Gaiman,