Salvaged Prayers

Jessica Brown

Where does the voice of a prayer come from? What swirling mass of the soul congeals to form syllables, words, utterances—spoken, or not, into a place we trust is more than us?

Where does the voice of a prayer come from? What swirling mass of the soul congeals to form syllables, words, utterances—spoken, or not, into a place we trust is more than us?

My prayers are often rote. I don’t know what soul-mass is congealing to form such flaccid and half-hearted, exhausted petitions. Help me. I’m tired. Thank you. God, my head hurts. Please help me. Oh Lord this is a hard day, help me.

Sometimes I hear my prayers more than at other times: the ear of my ears open, as it were, and I can hear things in my prayers: a strain of distrust, a lash of anger—and so often, the deep, structural levels of selfishness and ego: help me help me help me.

I try to form sentences that are more appealing:

But your will, Lord, not mine, tacked on to please please please please—

or, to feel less selfish, I toss in something like, help others too, help them, Lord, help the people who have to work in an office with such a headache as this . . .

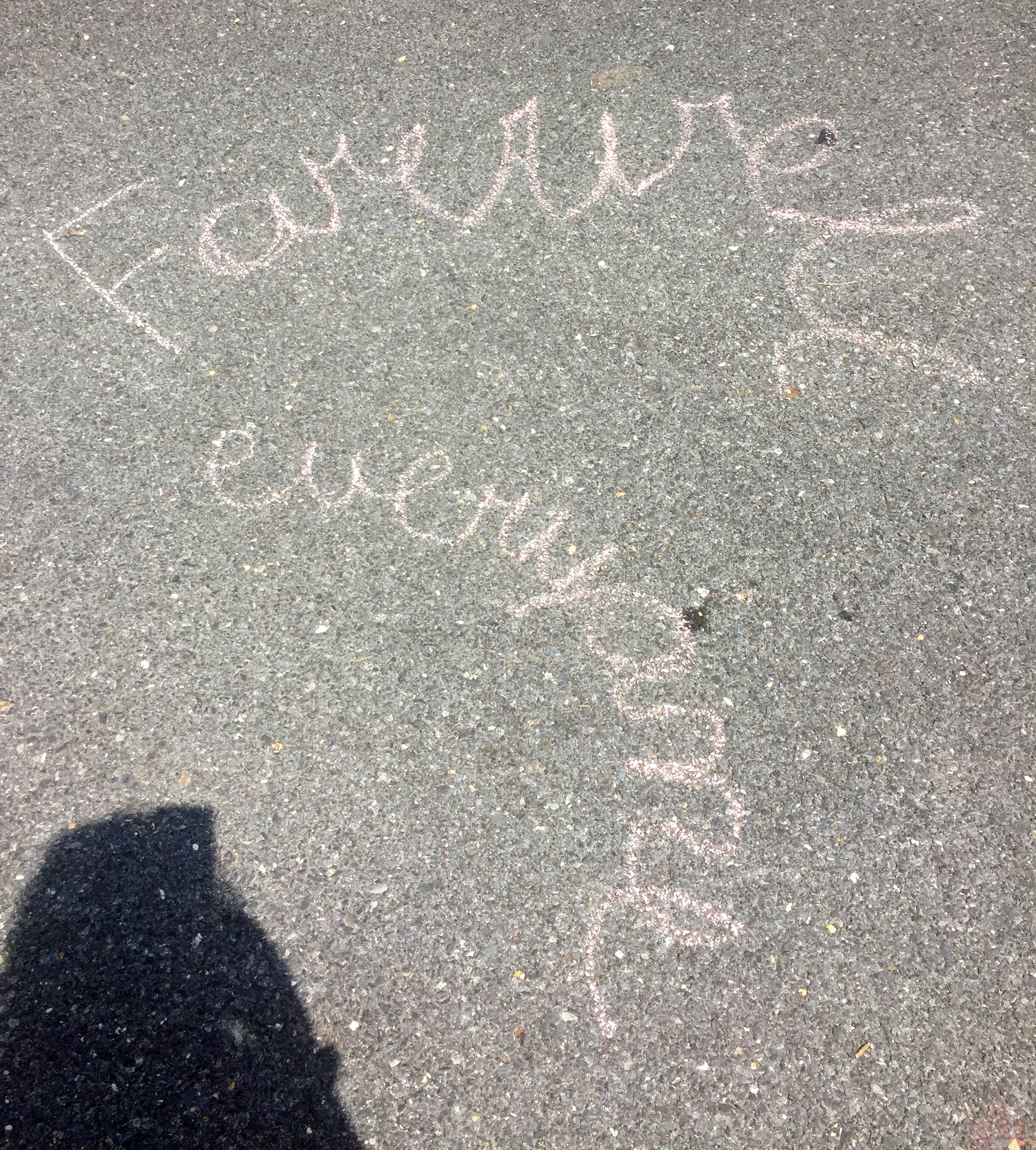

Sometimes the prayers come out as mean: oh my gosh God help me to forgive that crazy lady who can’t figure out how to run a computer and give me my refund . . .

or really angry: shit, God, how much more does this lady have to go through?—please just heal her already—what are you WAITING FOR—

or silly: ohpleaseGodhelpmestopdevoringthisbagofchips!

But mostly they’re just words rushed out from the quick of the brain, not looked at for any long time—it’s too painful, to stare at the meager, flinty words which expose such a lack of wisdom, kindness, balance, all that I want to pray with—slash and dash kind of prayers.

But, slowly, slowly, the ear of my ears, as it were, is opening to another level of sound: not just the immaturity of my prayers (that was one level of honesty) but to something else, something altogether beautiful (a deeper level of honesty, if you will).

And that’s the way God salvages our prayers.

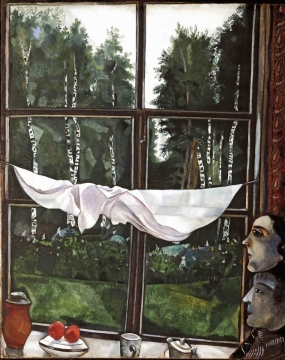

We humans salvage things. We glean and bring home and re-fashion. Ruth in the Bible walked behind the wheat pickers, gleaning the little grains left over in the wake. Some people know how to forage in forests and supermarket stalls alike. The best artists—be it songwriters, novelists, painters—see and hear things that others overlook, and tenderly these are brought home and re-worked into a narrative, or a sculpture, or a song.

The nonfiction film The Gleaners and I by Agnés Varda is a beautiful visual exploration of this human activity to glean and salvage—this capacity we have to forage, find, save, reuse, re-value. The potatoes that the potato farmers throw away because they do not fit the shape and size standards become sustenance for nearby gypsies. The heart-shaped potatoes are treasured and taken home by Agnes herself, who films them later slowly, lovingly. Agnes interviews people who find their food in trashcans or street refuse after open-air markets. She interviews others who take advantage of high storms and low tides to salvage all the oysters that the oyster-farmers don’t take. There’s a family who finds a disused vineyard. There’s a man who finds broken fridges, and brings them home to give to neighbors who need them.

One of the gleaners in the film describes what she does proudly, saying how her own mother taught her: “Pick up everything so nothing gets wasted.”

I re-watched the film recently, through this new prism of understanding how God salvages my prayers. It helped me realize that I can trust him to forage, find, save, reuse, and re-value the soul-stuff of my prayers. For if a human being can find such reusable worth and delight in something thrown away, how much more can God the primary Creator salvage from his beloved creation? These gleaners teach me about the tender, artistic, thrifty, imaginative nature of God’s listening ear to my prayers. When Agnes interviews the famous artist Louis Pons, who makes beautiful creations from refuse, he explains, “People think it’s a cluster of junk. I see it as a cluster of possibilities.”

This is the redemptive heart of salvaged prayer.

I think of my grandma Ruth, Dr. Ruth E. B. Smith, who saved up bits and tatters from the clothes that people in her family wore. Others might have thrown out or given away such clothing, but Grandma Ruth pieces together strips and squares to make vibrant, beautiful quilts. When I visit Texas, I sleep under one such quilt, and I know there are piece from my dad’s trousers and my mom’s prom dress woven into blanket keeping me warm.

I think of my father-in-law, who not only makes violins, but repairs them. One day, someone gave him a squashed, broken, moldy violin, asking him to do what he could with it. And Brendan repaired it. It didn’t go into the trash; it was carefully reworked and saved and made beautiful—made ready for music—again.

I think of my friend whose neighbor’s apples were all bruised on the ground and just starting to brown. Emilie brought them home in paper bags and made jars of chutney. They were not thrown in the waste bin, these apples; they were cut and stewed with onions and raisins, served out at mealtimes.

So, I think of my prayers, and then the Lord, salvaging everything. From out of my egocentric prayers, God salvages—maybe a plea for help that’s like robin eggshells, too fragile for breath but just right for a tempura mosaic.

From my angry prayers, does he gather red wool threads, dyed a little too dark for a sweater but perfect for a hot mitt?

From my silly prayer asking him to help me stop eating my chips while I’m stuffing my face: does he gather to himself a briar patch of desperation, good for telling stories about cheeky rabbits and other small creatures?

When I get lost in some meandering prayer-turned-soliloquy, almost forgetting entirely I’m not talking to myself about the miasma of my own problems—He never forgets we are in a dialogue. God gathers everything that has fallen to the ground, all the mussed and bruised words, the ripped and soiled sentences.

God creatively tucks them away, treasuring his lost finds, arranging and re-arranging until some startlingly lovely patterns emerge, designs made together in the merciful and beautifying dialogue of prayer.

I worked a number of positions in television news, and the only aspect of it I really enjoyed was the news writing. The experience taught me a great deal about the kind of writer I wanted to be. And until recently, I’d forgotten I’d wanted to be the kind of writer whose stories are read aloud. There’s a power in telling stories for all to hear.

I worked a number of positions in television news, and the only aspect of it I really enjoyed was the news writing. The experience taught me a great deal about the kind of writer I wanted to be. And until recently, I’d forgotten I’d wanted to be the kind of writer whose stories are read aloud. There’s a power in telling stories for all to hear.

Oh, oh, deep water—

Oh, oh, deep water—

The wren is a big song packed into a tiny brown dart of a body with an inquisitive personality. Looking, it hops and tilts its head in that stop-action way. And it instinctively sings what is beautiful within their prodigious range of sound. One interrupted a rest between notes in a bar of music I was playing. I got up immediately, forgetting my music, and moved to the window hoping for a glimpse.

The wren is a big song packed into a tiny brown dart of a body with an inquisitive personality. Looking, it hops and tilts its head in that stop-action way. And it instinctively sings what is beautiful within their prodigious range of sound. One interrupted a rest between notes in a bar of music I was playing. I got up immediately, forgetting my music, and moved to the window hoping for a glimpse. The evening I pulled into Ann Arbor, Michigan, a rainbow appeared as I put the car in park. No kidding, it was pouring down rain and then it wasn’t and six different rays of color soared above my Mazda 5 and sailed to the Pittsfield Township water tower a few yards away. “A rainbow!” I proclaimed as I stepped out of the car, a beautiful welcome on my move to a new town.

The evening I pulled into Ann Arbor, Michigan, a rainbow appeared as I put the car in park. No kidding, it was pouring down rain and then it wasn’t and six different rays of color soared above my Mazda 5 and sailed to the Pittsfield Township water tower a few yards away. “A rainbow!” I proclaimed as I stepped out of the car, a beautiful welcome on my move to a new town. Ever had one of those cool moments when, after reading about a favorite person, you suddenly receive this flash of insight? You feel one part shame for not seeing it before, but three parts satisfaction for at least coming to it eventually? Well, I should have seen this with

Ever had one of those cool moments when, after reading about a favorite person, you suddenly receive this flash of insight? You feel one part shame for not seeing it before, but three parts satisfaction for at least coming to it eventually? Well, I should have seen this with  Since my first timid slurp, rife with notes of Palmolive and expired milk, I have distrusted sour beer and all its enthusiasts. Each one has been served by a smirking bartender who addresses my splutter with a smug, “Yeah, it’s not for…everybody.”

Since my first timid slurp, rife with notes of Palmolive and expired milk, I have distrusted sour beer and all its enthusiasts. Each one has been served by a smirking bartender who addresses my splutter with a smug, “Yeah, it’s not for…everybody.”  When

When  Outside my kitchen window, a gingko tree

bursts gold, fan-shaped leaves shimmering

Outside my kitchen window, a gingko tree

bursts gold, fan-shaped leaves shimmering

On the first day of 7th grade my history teacher asked us to write down a nickname she should use for us in class. Did she mean we could choose a nickname we wanted to be called by? An Aaron by any other name? I had felt so penned in by name at 12. It had already been egregiously mispronounced (“erin”) and misspelled (I possess a litany of incorrect name tags). Back then I didn’t know of any really admirable Aaron’s either —

On the first day of 7th grade my history teacher asked us to write down a nickname she should use for us in class. Did she mean we could choose a nickname we wanted to be called by? An Aaron by any other name? I had felt so penned in by name at 12. It had already been egregiously mispronounced (“erin”) and misspelled (I possess a litany of incorrect name tags). Back then I didn’t know of any really admirable Aaron’s either —

I pretty much went back to work. Nothing beats reality.

—

I pretty much went back to work. Nothing beats reality.

— A friend of mine who wants to put baseboards in his house was told what it takes to do good baseboard work: a thousand cuts. I can’t tell if that’s a type of hope, as even the best get to be the best through tedium not talent, or a type of torture, viz., death by a thousand maddening cuts.

A friend of mine who wants to put baseboards in his house was told what it takes to do good baseboard work: a thousand cuts. I can’t tell if that’s a type of hope, as even the best get to be the best through tedium not talent, or a type of torture, viz., death by a thousand maddening cuts.